For Italian version please scroll down

In the aftermath of Brexit, while everybody worries about the consequences of the British referendum on European financial markets, while everyone worries about our freedom of movement, and wonders whether British citizens can continue working in the European community and vice versa—in a period of uncertainty and fear, not only about the world economy, but also about the deep cultural and religious conflicts that divide us—while the foundations of the Eiffel Tower are still trembling, and Parisians wait for the next

Bitte Coffeehouse

Glogauer Str. 6, 10999 Berlin

ISIS attack, as bombs continue to rain down on Syria—while democracy comes under serious threat in Turkey, not because of the coup but because of Turkey’s own President—while the permanent Middle Eastern conflict between Israel and Palestine continues to go unresolved—while migration from Arab countries grows increasingly critical—and while, in the USA, the possibility of a Trump victory in the presidential elections begins to truly terrify Democrats (and people around the world)—while all this is happening, in Berlin, something of an enclave in the middle of Merkel’s Germany, the atmosphere is different.

It’s as if this city has a unifying power. Unlike other multi-ethnic capitals, Berlin isn’t a wealthy city where people come to make their fortunes. In fact, although there are people from all over the world in Berlin — people who have escaped from harsh realities or immigrated to find work — the trend is the opposite. Naturally there are plenty of speculators who take advantage, as they have for years, of the favorable real estate prices. (These speculators restructure entire buildings, kicking out the former tenants, to sell or rent them at soaring prices.) Moreover, many people in Berlin are opening businesses — especially in the catering field — capitalizing on Berlin’s popularity and surging tourism. Nevertheless, a large proportion of the people who’ve moved to Berlin have arrived to engage in creative or artistic activities.

Bitte Coffeehouse

Glogauer Str. 6, 10999 Berlin

A colorful society

I have lived in this city for many years now, and over this period I’ve met people across the spectrum—ranging from businessmen to homeless citizens, from Muslims to Mormons. Although my experience is absolutely subjective, and specific to the areas where I move, I remain impressed by the volume of evidence that I’ve gathered about the people who choose to live in Berlin: they’ve come here because life is cheaper and, in some way, Berlin remains a place where you can still cultivate passions, work, and live on very little. This results in a relaxed atmosphere, promoting coexistence between people of different ethnicities, religions, and

Bitte Coffeehouse Glogauer Str. 6, 10999 Berlin

nationalities.For example, in the district where I live, there is a considerable Arab presence, as well as a large Turkish population that operates many of the commercial businesses. There are also large numbers of Spanish residents and Hispanic Americans, as well as considerable Polish, Italian, Greek, Serbo-Croatian and Anglo-Saxon populations—the latter stemming from three different continents. Although, from what I am able to discern, there isn’t a true integration of the majority of the Arab and Turkish populations, it’s equally true that there are no social tensions between these residents and the others. And even considering the partial detachment of the Muslim residents, who are nevertheless absorbed in the social and commercial life of the city, everyone coexists peacefully.

It wouldn’t be unusual to see, sharing the same bench, the most nostalgic variety of punks, a lady with a veil watching her kids at play, and two women kissing.

To get an idea of this phenomenon, you only need to look on Facebook, where you can search for the groups created by the different communities that live in Berlin:

Españoles en Berlín has nearly 20,000 members, Polacy w Berlinie has almost 19,000, Brasileiros em Berlin has 9,000, Русские в Берлине has nearly 7,000, Italiani a Berlino has 6,500, ישראלים בברלין Israelis in Berlin has over 6,000, Nederlanders in Berlijn has 6,000, Svenskar i Berlin has 5,500, Berlinli Türkler (merely one of many Turkish groups) has 5,000, Suomalaiset Berliini has 4,500, المثليين العرب في برلين (a group of gay Arab residents of Berlin) has 3,000, Danskere i Berlin has 3,600, Les français à Berlin has about 3,300 members, Romanii din Berlin has 2,000. Beyond this, there are countless groups for English-speaking residents in the German capital.

International friendships

Living in a society this diverse and colorful presents a number of advantages that exert a positive impact on my professional and social life. In my pilates classes, for example, attendees come from a wide variety of different countries.

Bitte Coffeehouse Glogauer Str. 6, 10999 Berlin

Among my friends—and I’m referring here only to my closest friends—are a Texan and his Danish girlfriend, a German/Croatian man and his Greek friend, a Southern German and his Venezuelan boyfriend, a lovely Anglo-Spanish woman, two Peruvians, an Israeli, an Iranian, and a Vietnamese-Canadian. And if I were to list the different encounters, the people I’ve flirted with, the people I’ve met at a bar or in the park, then the list would be far longer! This plurality, this diversity — in the best sense of the word — and this wealth of choice is reflected in every aspect of life. Because everyone in Berlin, even unconsciously, sows a seed of their own tree, a seed composed of the habits and flavors of their country of origin. They nurture the development of this microcosm without borders—a microcosm that is, ultimately, Berlin.

My friend Diego, for instance, despite the widespread tendency to lump all of South America into a single basket, or to refer to all its inhabitants as “Spanish,” is very keen to point out the significant differences between the various Spanish-language countries. He also often points out instances in which Peruvians are victims of prejudice or stereotypes. Chesco, who is also from Lima, introduced me (which was equally important for me) to their country’s flavorful cuisine and the pisco sour, a cocktail made from the distilled liquor pisco. I also often talk to Bobby about matters concerning the United States, or converse with Michael (an Israeli) or Ron (from Iran) about issues affecting the Middle East. This is an inspiring experience for me. I can’t think of many other places in the world where all this would be possible.

My friend Rosie, whose father is Spanish and mother is from London, used to help me improve my English. She would spend whole evenings talking to me only in English, and help correct my translations of my articles.

My friend Denis, with a German father and Croatian mother, is also someone I can trust entirely and count on for everything. He helps me navigate the German bureaucracy with his empathetic capacity—maybe because he’s not one-hundred percent German.

Thorsten, however, who is one-hundred percent German, helped me understand and appreciate the lakes and parks of Berlin, often telling me stories of a city that no longer exists. Then there’s Yiannis, not only a careful and sensitive friend, but also a “party animal” who is always surrounded by other Greeks like him, ready grab a beer or go dancing.

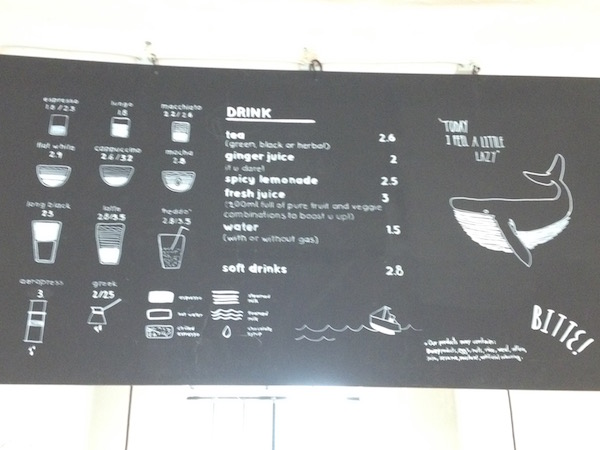

I often find myself with his group at Bitte Coffeehouse, a lovely cafe run by Christine and Markela. Since their bar is only a few steps from the studio where I teach pilates, often I’ll pass by just to give a kiss to the girls, as we call them, or meet other friends. Bitte Coffeehouse is a warm and welcoming place. The decor is simple: tables and stools are made of rough wooden planks. The entry sign, a beautiful drawing made by Markela, bears the face of a bearded sailor smoking a pipe. The cafe is always full of beautiful people, Greek kids, and excellent Greek products—and on Sunday, a special and fancy menu. Bitte is a concise (and precise) expression of the plurality of choices offered by a multi-cultural city.

However, I’m aware that even the most perfect balance is precarious, and history has shown that even the best companies may stumble if they don’t adapt their structure. I know that we live in a terrifying time, in which any fanatic can blow himself up in the middle of a city, or an angry homophobe can shoot dozens of people in a museum or nightclub (as happened in Orlando). But in an atmosphere of great tension and strong social insecurity, I like to be in a city where everyone lives under the same roof, a place where you can exchange between different cultures and generations—a place where we’re all a little different, but no one judges you, and what matters isn’t your passport, your lifestyle choices, or your appearance, but your respect for rules and for other human beings.

ITALIAN VERSION

In tempo di Brexit, mentre tutti si interrogano circa le conseguenze del referendum inglese sui mercati europei, sulla libera circolazione e sulle possibilità di lavoro dei cittadini britannici in Stati membri della comunità europea e viceversa, in un periodo di incertezze e paure non solo legate all’economia mondiale ma anche a profondi conflitti culturali e religiosi, mentre a Parigi le gambe della Tour Eiffel tremano in attesa del prossimo attentato dell’Isis e sulla Siria continuano a piovere bombe, mentre in Turchia viene seriamente minacciata la democrazia, non dai golpisti bensì dal capo di governo, e poco distante non si risolve ancora l’atavica questione mediorientale tra Israele e Palestina, mentre è sempre più critico il flusso migratorio dai Paesi arabi, e negli USA la possibile vittoria di Trump alle elezioni presidenziali inizia a spaventare i democratici (…e non solo loro), a Berlino – per certi aspetti quasi una enclave nella Germania della Merkel – si respira un’aria diversa.

È come se questa città avesse un potere aggregante.

Bitte Coffeehouse Glogauer Str. 6, 10999 Berlin

A differenza di altre capitali multietniche, Berlino non è una città ricca dove si viene a far fortuna e, sebbene ci siano persone da tutto il mondo che sfuggono da realtà difficili o che vengono per trovare lavoro, il trend è opposto. Certo, non sono poco gli speculatori che da anni approfittano dei prezzi ancora vantaggiosi del mercato immobiliare per ristrutturare interi palazzi rimettendoli sul mercato a prezzi vertiginosi e con affitti sempre più alti, così come non sono pochi coloro che hanno aperto attività, soprattutto nella ristorazione, puntando sulla popolarità di Berlino e sul turismo, ma ciò nonostante, sono numerosissimi quelli che vi si trasferiscono per dedicarsi ad attività creative o artistiche.

Bitte Coffeehouse Glogauer Str. 6, 10999 Berlin

Oramai vivo qui da anni, e in questo tempo ho conosciuto persone in modo trasversale, dal professionista al senza tetto, da musulmani a mormoni. Ora, pur essendo la mia esperienza assolutamente parziale e relativa agli ambiti in cui mi muovo, è impressionante come la maggior parte delle testimonianze che ho raccolto è di gente che ha scelto di vivere a Berlino perché la vita costa meno e, in qualche modo, è ancora possibile coltivare passioni, lavorare e vivere di poco.

Una città multiculturale

Questa peculiarità determina un clima disteso che favorisce la convivenza tra persone di diverse etnie, religioni e nazionalità.

Nel quartiere dove abito, per esempio, c’è una massiccia presenza araba, e in particolare turca, che gestisce moltissime attività commerciali, ci sono anche tantissimi spagnoli o ispano americani, polacchi, italiani, greci, serbo-croati e anglosassoni provenienti da tre diversi continenti.

Almeno per quello che mi è dato vedere, se è vero che non esiste una reale integrazione da parte della maggioranza degli arabi, è altrettanto vero che non esistono tensioni sociali. E pur considerando il parziale distacco dei musulmani, che sono comunque assorbiti nel tessuto sociale e lavorativo della città, tutti convivono pacificamente.

Seduti sulla stessa panchina, è possibile vedere il più nostalgico dei punk, una signora col velo che guarda i bambini giocare e due donne che si baciano.

Bitte Coffeehouse Glogauer Str. 6, 10999 Berlin

Per avere un’idea di questo fenomeno, basta andare su Facebook e cercare i gruppi creati dalle diverse comunità residenti a Berlino:

Españoles en Berlín conta quasi 20.000 membri, Polacy w Berlinie ne ha quasi 19.000, Brasileiros em Berlin 9.000, Русские в Берлине circa 7.000, Italiani a Berlino 6.500, ישראלים בברלין Israelis in Berlin più di 6.000, Nederlanders in Berlijn 6.000, Svenskar i Berlin 5.500, Berlinli Türkler (solo uno dei tantissimi siti di gruppi turchi a Berlino) 5.000, Suomalaiset Berliini 4.500, المثليين العرب في برلين . (gruppo di soli omosessuali arabi a Berlino) 3.000, Danskere i Berlin 3.600, Les français à Berlin con circa 3.300 membri, Romanii din Berlin 2.000, più un numero imprecisato di gruppi per anglofoni residenti nella capitale tedesca.

Amicizie internazionali

Vivere in una società così variegata e colorata ha tutta una serie di vantaggi che si ripercuotono positivamente anche sulla mia vita professionale e sociale.

Bitte Coffeehouse Glogauer Str. 6, 10999 Berlin

Alle mie classi di pilates hanno partecipato e continuano a venire persone provenienti da tantissimi Paesi diversi.

Tra le mie amicizie, e mi riferisco soltanto alle più strette, ci sono un ragazzo texano e la sua compagna danese, un ragazzo tedesco/croato e il suo compagno greco, un ragazzo della Germania del Sud e il suo ragazzo venezuelano, una dolcissima ragazza anglo-spagnola, due ragazzi peruviani, un israeliano, un iraniano e un vietnamita/canadese.

Se poi dovessi elencare gli incontri, i flirt e le persone conosciute in un bar o al parco, allora la lista sarebbe molto più lunga!

Questa stessa pluralità, diversità – intesa nell’accezione migliore del termine – e in un certo senso possibilità di scelta, si riflette in ogni aspetto della vita, perché ognuno, anche in modo inconsapevole, gettando un seme del proprio albero, fatto di abitudini e sapori del Paese d’origine, favorisce lo sviluppo di questo microcosmo senza frontiere (che è Berlino,) dove è possibile la massima condivisione.

Il mio amico Diego, per esempio, a dispetto della tendenza molto diffusa di parlare del Sud America come di un unico grande contenitore o di riferirsi a tutti i suoi abitanti come a spagnoli, ci tiene molto a sottolineare le significative differenze tra le numerose nazioni ispaniche, così come non manca mai di esporre il suo punto di vista su questioni che vedono i peruviani vittime di pregiudizi o di luoghi comuni e Chesco, anche lui di Lima, mi ha fatto conoscere, cosa per me altrettanto importante, la loro saporitissima cucina e il pisco sour, un cocktail a base di pisco, un liquore distillato.

Anche parlare con Bobby sulle faccende che riguardano gli Stati Uniti oppure confrontarmi con Michael, israeliano, o con Ron, iraniano, su questioni che interessano il Medioriente, è un’esperienza per me stimolante che non so in quanti altri posti sarebbe possibile.

Rosie, padre spagnolo e madre londinese, per aiutarmi a migliorare la lingua, trascorre intere serate parlando con me esclusivamente in inglese e corregge sempre le traduzioni che faccio dei miei articoli.

Il mio amico Denis, padre tedesco e madre croata, oltre ad essere una persona con la quale mi confido e sulla quale posso contare per ogni cosa, mi aiuta a districarmi nella burocrazia tedesca con la sua capacità di comprensione, quella di chi tedesco al 100% non è. Thorsten, invece, tedesco al 100%, mi ha fatto conoscere e apprezzare parchi e laghi di Berlino, raccontandomi spesso di una città che oggi non c’è più. Poi c’è Yiannis, non soltanto un amico attento e sensibile, ma anche “festaiolo”, sempre circondato da tanti altri ragazzi greci come lui, pronti a bere una birra o ad andare a ballare.

Con loro spesso ci si ritrova al Bitte Coffeehouse, un delizioso caffè gestito da Christine e Markela.

Dato che il loro bar si trova a pochi passi dallo studio in cui insegno pilates, capita spesso che vada a dare un bacio alle girls, come le chiamiamo, oppure che mi veda lì con altri amici.

Il Bitte è un posto accogliente e familiare. L’arredamento è essenziale. Tavole e sgabelli sono fatti con assi di legno grezzo. L’insegna, un bellissimo disegno fatta da Markela, è il volto di un barbuto marinaio che fuma la pipa. C’è sempre tanta gente carina, moltissimi ragazzi greci ma non solo, tanti ottimi prodotti ellenici, e la domenica, menu speciali e fantasiosi.

Il Bitte è proprio l’espressione della pluralità di scelte che ti offre una città multi culturale.

Ora, so bene che anche il più perfetto equilibrio è assolutamente precario e, come la storia insegna, anche le migliori società possono vacillare per un minimo cambiamento del loro assetto. So bene che viviamo in un periodo terribile, in cui il primo fanatico può farsi esplodere in una metropolitana o qualche omofobo fucilare decine di persone in un museo o in una discoteca così com’è accaduto a Orlando, ma in un clima di grandi tensioni e forti insicurezze sociali, mi piace essere in una città in cui si vive tutti sotto lo stesso tetto, un luogo in cui è possibile uno scambio tra differenti culture e generazioni, dove si è tutti diversi, nessuno ti giudica e ciò che conta non è il tuo passaporto, le tue scelte di vita e nemmeno le apparenze, ma il rispetto delle regole e degli altri.